This article is adapted from a speech given by CCAO's communications coordinator, Wesley Cocozello

“Climate change should be a top priority for the Catholic Church if the church really believes that its mission is for the flourishing of the life of the world.” -Fr. Sean McDonagh, SSC

At first blush, environmental justice may sound nonessential to a life of faith. Many Catholics aren’t exposed to spiritual reflections on God’s creation or questions of environmental care at mass or during formation programs like confirmation or RCIA. When the conversation does come up, some argue that environmental justice is just not as important as other pressing concerns.

I’d like to introduce you to two members of God’s creations that I hope will challenge these attitudes.

The first is Salma Adeel from Pakistan. The second is the Great Barrier Reef from Australia.

Salma was a wife and mother of three living in the city of Karachi when a record-breaking heat wave hit in June, 2015.

Her husband was a painter who whitewashed houses and other buildings. He made decent money and their family was happy. But during that heat wave, he died from dehydration and heat stroke.

More than 2,000 other people died too. 65,000 people were treated for illness.

All these casualties happened within one week.

“It was very shocking,” Salma said. “The first few months were very tough when there was no one to support us. I never imagined that one day I would have to go and do an outside job. [Now], I work nine hours a day, and some days I work overtime to make ends meet."

Access to safe drinking water is a problem in Pakistan. More frequent and extreme heat is making that problem worse.

If you’re thinking the obvious, yes, it’s true, Pakistan is a hot country, climate change or not. Climate change didn’t create the initial problem, but it has put it on steroids.

Over the last five decades, the annual average temperature in the country has gone up by roughly .5 degrees Celsius (which is 32.9 degrees Fahrenheit). Over the last three decades, the number of heatwave days per year have gone up fivefold.

The basic science of climate change is this: Our atmosphere is a certain “thickness,” which traps a certain amount of heat coming off the Earth. By adding greenhouse gases, primarily through the burning of fossil fuels, into the air, our atmosphere gets “thicker” and traps more heat.

Think of it this way: imagine you’re sleeping with one blanket on during the early part of summer. Your grandma comes in and adds a second blanket. As a result, you wake up in a sweat.

This is a very basic description of how the process works. That places like Karachi would be getting warmer then is an obvious consequence of climate change.

But the Catholic Church isn’t only interested in science. It’s also interested in justice.

The World Resource Institute has ranked each country in the world based on who emits the most greenhouse gases. Pakistan doesn’t break into the stop fifty. Historically, the country’s population has contributed less than one percent of the world’s greenhouse gasses.

And yet, according to the Global Climate Risk Index, Pakistan is among the top ten countries most affected by climate change. Poverty makes this situation more difficult to manage. Pakistan has the lowest “Human Development Index” in Asia.

Because of climate change, a phenomenon she has practically no responsibility for, Salma’s husband is dead. Because of climate change, she is single mother, and struggles to support her family by working in a garment factory.

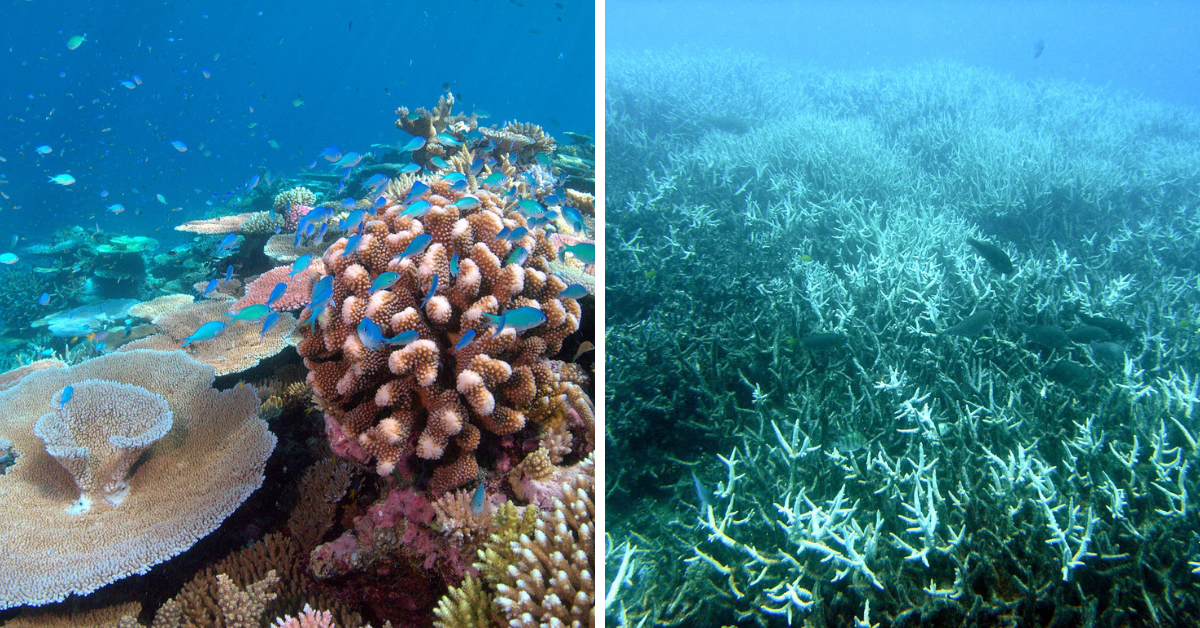

The second member of God’s creation I want to introduce you to is the Great Barrier Reef. It’s the world’s biggest single structure made by any living organisms, humans included. It’s so big that astronauts can see it from space. They’ve called it “the world’s most beautiful necklace.”

Since 2014, however, the reefs have been suffering from extensive coral bleaching.

Coral bleaching occurs when the algae living in an endosymbiotic relationship with the coral is expelled from the coral tissue. The algae provides up to 90 percent of the coral’s energy as well as its mardi gras array of colors.

A poison cocktail of ocean acidification and warming water (caused by climate change) are the primary culprits for the algae’s expulsion. With the algae gone, the coral limps along until it finally dies from starvation.

You might be thinking, “coral bleaching can happen naturally.” You’re right. Hurricanes and animal predators have caused it before.

But marine biologists agree that this most recent bout of bleaching is human-caused. What’s been happening since 2014 is the most severe and widespread coral bleaching ever recorded in the Great Barrier Reef.

To put the damage into perspective, researchers from the James Cook University in Australia indicate that as of 2017 coral bleaching stretches along two-thirds of the Reef - an area about the size of Italy.

Healthy coral vs. bleached coral

What do both of these stories illustrate? The people - and the creatures - most impacted by climate change are the least responsible for it.

What’s more, these people disproportionately live in poverty or are members of vulnerable communities. That especially is why the Catholic Church cares about environmental issues.

Our scriptures remind us over and over again that God is profoundly concerned about the wellbeing of the poor and marginalized.

A couple years ago I would have heard these two stories and not thought twice about them. It’s like hearing about the car crash or the apartment fire on the five o’clock news.

The danger with how we consume the news though is that the stuff of life shouldn’t be a footnote on our hour before dinner.

“Our goal is not to amass information or to satisfy curiosity, but rather to become painfully aware, to dare to turn what is happening to the world into our own personal suffering and thus to discover what each of us can do about it” (LS, 19).

When I first read those words from Pope Francis’ encyclical, Laudato Si’, in 2015, it felt like that he was challenging me personally. As someone who was (and still kinda is) uncomfortable with vulnerability, taking on someone else’s suffering is, to be frank with you, one of the things I’m most terrified of.

At a certain point in my life, it somehow became easier for me to trade in the mardi gras colors of life for easy comforts and a “go with the flow” attitude. But what I found in my own spiritual life is that when I shut out pain and vulnerability, I shut out joy and hope too.

As Pope Francis has said, this spiritual numbness is at the root of the problem Salma and the Great Barrier Reefs are facing today.

In other words, why do the concerns of the poor and the suffering go unaddressed?

“[It] is due partly,” the Pope says, “to the fact that many professionals, opinion makers, communications media and centers of power, being located in affluent urban areas, are far removed from the poor, with little direct contact with their problems. They live and reason from the comfortable position of a high level of development and quality of life well beyond the reach of the majority of the world’s population. This lack of physical contact and encounter can lead to a numbing of conscience and to tendentious analysis which neglect parts of reality” (LS, 49).

If you think the Pope is being original here, he isn’t. Jesus said basically the same thing when he criticized the comfortable people of his day.

The Pharisees, Jesus said, “tie up heavy burdens [hard to carry] and lay them on people’s shoulders, but they will not lift a finger to move them. They lengthen their tassels and love places of honor at banquets and greetings in the marketplaces” (Matthew 23: 4 – 6).

Per usual because he’s a troublemaker, it’s Jesus, not Pope Francis, that offers the more damning critique. Because unlike a car crash or an apartment fire, the thing that killed Salma’s husband and is killing the Great Barrier Reef is doing so because of us.

In the United States, according to National Geographic Greendex study, five percent of the world’s population burns a quarter of the world’s oil and twenty-three percent of the world’s coal.

We are the Pharisees tying up heavy burdens too hard to carry and laying them on other people’s shoulders. We are by no means the only one, but for how long will we continue to deny the consequences of our actions and neglect the poor whom God loves who much?

How long can we hear the “cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” and not cry alongside them?

The first half of Pope Francis’ challenge is “to dare to turn what is happening to the world into our own personal suffering.” That is a challenge of the imagination, and of the soul, which we must wrestle with every day.

But there is a second part to the challenge: “and thus to discover what each of us can do about it.”

What can we do about it? The Church offers us two signposts.

The first is to practice solidarity. To paraphrase St. Pope John Paul II, solidarity is the faithful and persistent determination to act as each other’s keepers. This, in itself, is a paraphrase of the Cain and Abel story (Genesis 4: 1 – 16).

“Where is your brother Abel?” God asks.

“I do not know. Am I my brother’s keeper?” Cain replies.

The fact that we continue to model our behavior after Cain is why climate change exists in the first place. Back when we started burning fossil fuels, we couldn’t have known the full extent of the consequences. Now we do – if we care to listen we’ll hear the cries of our sisters and brothers dying from extreme heat or slow starvation.

But we’ve said, “not my problem.”

God is constantly reminding us that it is.

“Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground” God says. “Now you are banned from the ground. If you till the ground, it shall no longer give you its produce.” It won’t be very long before this curse from an allegory becomes a pretty good description of actual events.

How can you stand in solidarity then? The first step is to develop friendships with people in impacted communities. You can do this through mission trips and volunteering, either abroad or locally. You can watch documentaries and seek out peoples’ stories online.

While you’re doing this though, remember St. Columban: “a life unlike your own can be your teacher.” They are the teacher and you are the student.

However, you can’t stop there. Solidarity is also about action or else it’s becomes an empty promise. So what can you do? Talk about the experience of your new friendships with others, either in person or on social media. Stand up for them when it counts, which leads us to…

The second signpost from the Church is to put the common good above your own good. This does not mean ignoring your own good. Instead, be like the farmer in the famous reading from Deuteronomy: “when you are harvesting in your field and you overlook a sheaf, do not go back to get it. Leave it for the foreigner, the fatherless, and the widow” (Deuteronomy 24: 19). In other words, harvest what you need for yourself, but always keep in mind the needs of other people.

This should not be new for Catholics. We have a long tradition of fasting and asceticism and one of its purposes has always been to identify with the poor and more justly use the resources of the earth.

We need to reclaim this aspect of our spiritual tradition and practice it at the personally and the societal level. We also need to practice it outside the forty days of Lent.

Again, with less than five percent of the world’s population, the United States uses a quarter of the world’s oil and twenty-three percent of the world’s coal. Isn’t that gluttony? And how fair is it to the rest of the world?

We must remember that the goods of creation are destined for all members of creation. The Church calls this the universal destination of goods. Everything fundamentally belongs to the one who made it (that is, God), and God explicitly desires that everyone share the bounty of God’s creation. Everyone - not just a few - must flourish.

Another world is possible. That is the promise of the Kingdom of God. We can have a world where husbands return home to their wife and children. We can have a world where ““the world’s most beautiful necklace” stays beautiful.

But God requires our cooperation. Without our participation, there is no better tomorrow.

Copyright © 2025 Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach, Washington, D.C.