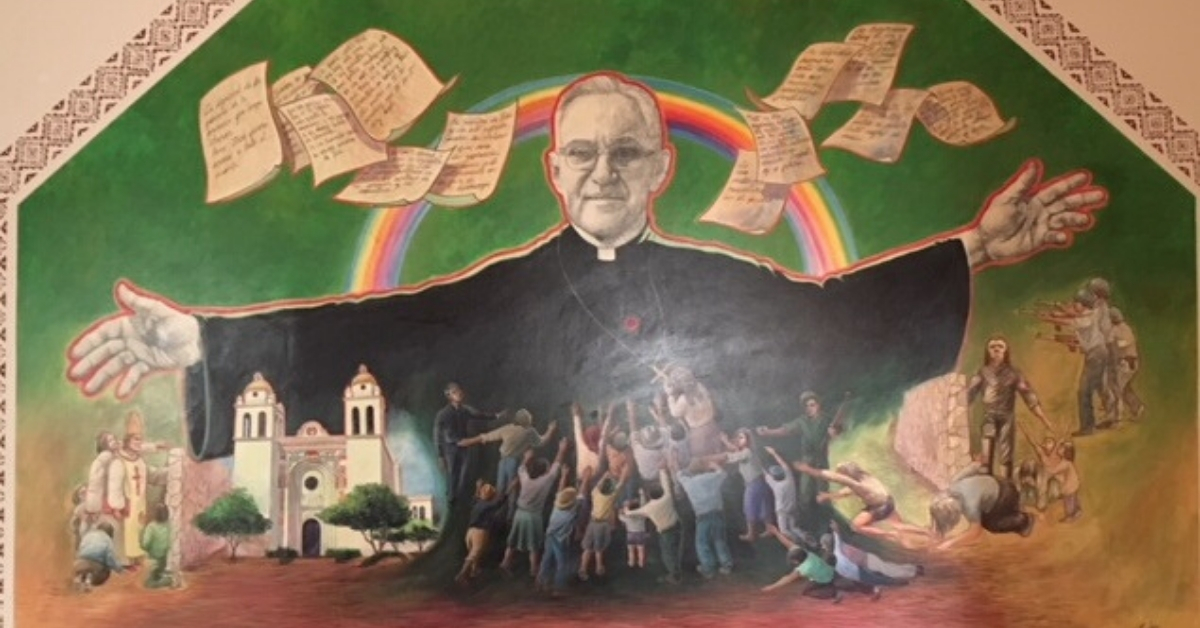

A mural of St. Oscar Romero in the Columban Mission Center in El Paso, TX

By Scott Wright, Director, Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach

Easter is itself now the cry of victory. No one can quench that life that Christ has resurrected. Neither death nor all the banners of death and hatred raised against Him and against His church can prevail. He is the victorious one! Just as He will thrive in an unending Easter, so we must accompany Him in a Lent and a Holy Week of cross, sacrifice and martyrdom. As He said, ‘Blessed are they who are not scandalized by His cross.’ – Saint Oscar Romero, March 23, 1980

The coronavirus has brought us together as a human family as no other event in recent time. In the United States, some of us may still remember stories from our parents or grandparents of the Great Depression and the Great Flu Epidemic of 1918 that killed 50 - 100 million people worldwide. But now we face a future in which the entire planet is impacted by the great pandemic, and the poor and unemployed, the homeless and inmates in prison, seniors in nursing homes as well as persons with underlying health conditions are the most vulnerable.

While we look forward to Easter as “a cry of victory,” we must also accompany Christ in the “crosses,” and the “sacrifices” that the poor, and perhaps our neighbors and loved ones, will endure on a massive scale in the very near future. In the wake of this global pandemic, nations are also closing their borders to migrants and refugees fleeing wars and political violence, as well as hunger and starvation.

We have often heard it said that nations have the right to regulate their borders, but that rationale should not be based on narrow considerations of self-interest much less prejudice and hatred. Nations also have an obligation, and in the case of the United States, a legal obligation, in light of the U.S. Refugee Act passed by Congress 40 years ago, to hear the asylum claims of migrants and refugees fleeing for their lives, and to not deport them back to countries to face certain death. We must balance the right to control our borders with the moral and legal obligation to protect human lives, giving priority to the sanctity of life and our obligation to protect it.

Today we celebrate the 40th anniversary of the martyrdom of one of the church’s great saints and defenders of human life, Salvadoran Archbishop and now Saint Oscar Romero. In his last Sunday mass, Archbishop Romero preached a powerful homily in defense of human dignity and human rights. The Gospel reading for the day was about the crowds who wanted to put to death a woman who had broken the law and committed adultery. Today, with a deeper awareness of sexual abuse and domestic violence, we must also ask, “But what about the man? Didn’t he break the law, too?”

What if we substituted in this reflection the thousands of migrant and refugee families who are not permitted to seek asylum or are forced to wait in overcrowded and unhealthy conditions on the Mexican side of the border. They are accused of breaking the law, illegally crossing borders or seeking to do so, often at great risk, to protect and save their lives and the lives of their children. And like the woman in the Gospel reading, they too are under the threat of certain death, with little protection as they wait at the border, and even greater risk to their lives if they are deported back to the violence or hunger they had fled in Central America and Mexico.

Nothing is as important to the Church as human life, especially the lives of the poor and the oppressed. Jesus said that whatever is done to the poor is done to Him. This bloodshed, these deaths, are beyond all politics. They touch the very heart of God. – Saint Oscar Romero, March 16, 1980

Jesus asks the woman’s accusers: “Who among you is without sin?” For us today, we could ask as well, “Who among us does not have ancestors who sought refuge in our country?” We, too, would be forced to drop our stones and walk away in shame. The only people who could reply “No” would be our Native American or African American sisters and brothers, who either were here to begin with, or were forcibly enslaved and brought here against their will. Today, the sins of genocide and slavery are still being visited upon subsequent generations. We see this already as universities and cities across the nation begin to deal with their hidden and painful past histories of racism and violence. We are being called to find creative ways to address these crimes and seek reconciliation, based on truth, justice and moral and economic reparation.

Thirty years ago, “globalization” was the word for human progress, and promised to bring global prosperity to all. But that promise has not been fulfilled. For the migrants and refugee families at our southern border, globalization was a disaster, because it meant that U.S. agribusiness dumped heavily subsidized grain into Central American and Mexican markets, threatening the livelihood of millions of local farmers. Corporations extracted precious resources and exploited cheap labor in ways that have further impoverished the people of these countries. Corrupt governments, violent gangs and drug cartels have taken advantage of weak democracies, further driving migrants north to our southern border. Corporations, not people have benefited, as family farmers and workers in the U.S can testify.

Even though globalization was clothed in the language of an economy of abundance, it has turned out to be an economy of scarcity for the majority of the world’s poor because of the great inequality favoring wealthy corporations inherent in the system. Adapting an expression from Dr. Martin Luther King, the “promissory note” that the world’s poor holds on human dignity and economic security was returned to them marked “insufficient funds.” Today, Rev. William Barber of the Poor People’s Campaign is not shy about pointing out that 140 million people of all races in the U.S. are still poor, living paycheck to paycheck, and with the collapse of the global markets in the wake of the global pandemic, that number is about to grow exponentially.

What is at stake in this global pandemic is human dignity, solidarity and the common good. How will the most vulnerable sectors of our human family fare in this time of great peril?

In the faces and stories of migrants and refugees held hostage at the border, in the dignity and the compassion with which they compose themselves in their desperation, and in the solidarity that they show to one another, we see a mirror of our own fidelity to the Gospel, or indifference to our neighbor.

The Parable of the Last Judgment in the Gospel of Matthew (25:31-46), however, is addressed not to individual persons but to nations. If the judgment were only upon persons, we could breathe a sigh of relief, because there are magnificent examples of accompaniment and solidarity among our people, Christian, Jewish and Muslim, as well as people of good will, helping the migrants and refugee families. But the parable is addressed to “the nations”: “For I was a stranger… and you welcomed me.” It is up to us as a nation to decide how we will be judged.

In the prophetic words of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, himself a Jewish refugee from the Holocaust and colleague of Martin Luther King, Jr. in the civil rights movement: “Morally speaking, there is no limit to the concern one must feel for the suffering of human beings. Indifference to evil is worse than evil itself, and in a free society, some are guilty, but all are responsible.”

A Church that doesn’t provoke any crises, a Gospel that doesn’t unsettle, a Word of God that doesn’t get under anyone’s skin, a Word of God that doesn’t touch the real sin of the society in which it is being proclaimed – what Gospel is that? Very nice, pious considerations that don’t bother anyone, that’s the way many would like preaching to be. Those preachers who avoid every thorny matter so as not to be harassed, so as not to have conflicts and difficulties, do not light up the world they live in … The Gospel is courageous, it’s the Good News of him who came to take away the world’s sins. – Saint Oscar Romero, April 16, 1978

Archbishop Romero also spoke of the need to illuminate the troubled times he lived in with the light of the Gospel, squarely facing both the hopes and fears of the people facing an uncertain future: “No one,” he said, “should take it amiss that we illuminate our social, political and economic realities by the light of the divine Word … This is how the Gospel must be preached.” There is, in his words, “a political dimension” to the Gospel.

Human dignity and the common good are inseparable, and both are values that inform and judge our politics. We are not often used to addressing the great political, social and economic issues of our time with religious language, such as sin and salvation. But Archbishop Romero did so, speaking to a national audience by way of radio stations that carried his Sunday homilies into the poorest rural and urban homes of El Salvador and throughout Latin America. Granted, he was preaching the Gospel in a church, but it was a Gospel that illuminated and judged the political projects of his day.

What have we learned from the global pandemic in this time of global challenge and tragedy? Can we begin to address the public health crisis in our country, or throughout the world? What about the global existential threats of climate change and nuclear war, massive poverty and global migration?

Turning to the crisis we face today: “How are we as a nation or as a global community addressing the urgent challenges of the global pandemic?” “How are we addressing the growing hardship of a global economy in collapse?”

These are the great questions being debated now in Congress, in the media, and in homes and neighborhoods, cities and states, across the country. The coronavirus is a public health emergency that is putting potentially hundreds of thousands and perhaps millions of lives in danger – especially the lives of the poor, the migrants and refugees among us, and those who have underlying health conditions or little or no access to medical care. The global pandemic has made visible the hidden and systemic inequality and unpreparedness of public health systems across our country and the globe.

As our nation’s political leaders debate how to respond to the global pandemic and the collapse of the global economy, we can ask whose interests and whose lives are at stake? Which proposals defend the human dignity of the poor and those most impacted by the pandemic and economic crisis? Which proposals address the structural crisis of our public health system and our economy and look for opportunities to restructure them in ways that are more just, equitable and sustainable?

We must never again believe the excuse that politicians offer that “It can’t be done,” or “We don’t have the resources.” We know that our nation has spent trillions of dollars on wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and that the banks and corporations that were “too big to fail” in 2008 were bailed out in the last Great Recession, while the poor and working poor, particularly African Americans and Latinos, lost their homes and with them their dreams for education and health care for their families and children.

We can provide quality health care for all, if we have the political will to do so, prioritizing the lives of the poor and our children over the profits of the health insurance and pharmaceutical industries. We can rebuild the crumbling infrastructure of our country, including access to clean water, and provide jobs to many who are or soon will be unemployed, if we have the will to do so. This is not partisan politics, but rather the politics of human dignity and the common good.

We can end global warming, if we have the political will to do so, rejoining the Paris Agreement and prioritizing the lives of the poor and future generations over the profits of the fossil fuel industry. And we can end the threat of nuclear war and trillions of dollars of military expenditures if we have the political will to consider nonviolent and just peace alternatives to war. These are not naive proposals, but realistic responses to global existential threats to our planet and to future generations.

“I am very glad that just at this moment of crisis many who were asleep have awakened and at least ask themselves where the truth is to be found. Look for it. St. Paul shows us the way: with prayer, with reflection, appreciating what is good. These are wonderful criteria. Wherever there is ‘what is noble, what is good, what is right,’ there is God (Phil 4:8). If, besides these natural good things, there is found grace, holiness, sacraments, the joy of a conscience divinized by God, there is God.” – Saint Oscar Romero, October 8, 1978

Even in the midst of a cruel civil war that eventually took the lives of 75,000 people, and forcibly displaced over a million people, Archbishop Romero communicated a radical sense of hope, rooted in his conviction that “the hand of God [is] at work in the historical journey of the people.” That is why he keeps repeating that those who are working for justice “should never lose sight of this transcendent dimension.” God is at work in history. God sustains history. We are not alone. God will not abandon us. But we must also do our part.

In his last Sunday homily, responding to the prophet Isaiah’s promise to the people of Israel in exile in Babylon “to make all things new,” Archbishop Romero shed light on the challenges of his own day and concluded: “History will not fail … God sustains it.” For Romero, the great task of Christians is to contribute to building God’s kingdom by transforming history in ways that reflect the Beatitudes and those kingdom values: “Any historical project not founded on … the dignity of the human person, the will of God, the kingdom of Christ among us,” will not last.

For Romero, the words of Saint Paul in the Sunday readings sums up for him the call that Christians must heed, especially during this time of Lent when we are called to come back to our faith: “My desire is to know Christ and the power of his resurrection, and to share in his suffering by dying as he died in order one day to be raised from the dead” (Phil 3:10-11).

May this be our hope, as well, in these challenging times of a global pandemic and global economic collapse. We have choices to make now, and challenges to face as we seek to find ways to be compassionate, to help those who are faced with tragedy or unemployment, and above all to pray. This pandemic will, God willing, end one day. We must not lose this opportunity, nor return to our old ways. This is a moment of Kairos, a crucial opportunity to respond to God’s call to build a world more in conformity with the Beatitudes and the values of the Gospel. Another world is possible, if only we will make it so.

In this Season of Lent, when we journey with the human family during this difficult time of global pandemic, we may take heart from those who the Church has proclaimed as saints and martyrs, and concretely, from the wisdom and the witness of Salvadoran Archbishop and now Saint Oscar Romero, on the 40th anniversary of his martyrdom. He was assassinated at the altar for speaking truth to power and taking the side of the poor. In this time of global pandemic, may we make our own his Gospel courage and his radical hope in a God of life who is always at our side, calling us to a radical love beyond our fears.

Copyright © 2025 Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach, Washington, D.C.