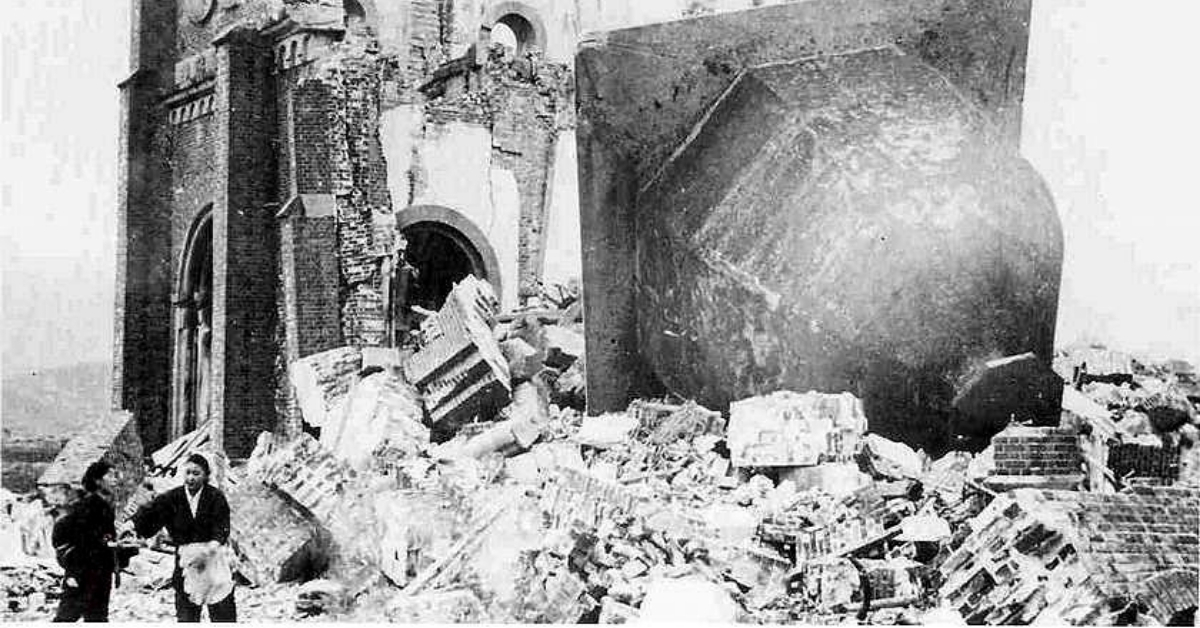

Urakami Catholic Cathedral in Nagasaki (January 1946), Wikimedia Commons

by Scott Wright

The Missionary Society of St. Columban and its missionary priests have witnessed the ravages of war and violence over the past century. Nearly two dozen Columbans were martyred in China, Myanmar, the Philippines and Korea prior to and during the Second World War and the Korean conflict, choosing to remain with their people rather than to flee. This lived experience of war led them, already in 1982, to respond to the threat of nuclear war in these words pronounced at their General Assembly:

“Our understanding of Christian discipleship leads us to condemn in strongest terms defense policies that every day make life more insecure. The most blatant of these are present policies of nuclear armament which threaten all life. These policies are themselves a form of killing since they consume resources desperately needed to meet basic human needs.”

This week marks the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings by the United States of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9). By the end of the year, 1945, more than 210,000 people, mainly civilians, were dead. Those who survived the bombings and their children continue to suffer the physical and psychological impacts of the bombings and the radiation.

Today, seventy-five years later, the nuclear sword of Damocles continues to hang over the world and to threaten a nuclear holocaust. The challenge is formidable. Yet we have not given up hope. Three years ago, the world moved one step closer to a nuclear weapon free world when 122 nations signed the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. None of the nine nuclear nations signed, but the message from the rest of the world was clear. Currently, forty nations have ratified the treaty; fifty nations are needed for the treaty to go into effect.

The impassioned cry for life of people standing up for justice and calling for peace resounds across the planet. Their hope and ours hastens that day of peace and is both a gift and a challenge. That is the promise we hold on to, the arc of the moral universe that is long but bends toward justice, and the victory of God’s redemptive love over violence on the cross. That is the message we proclaim, the urgent need to affirm Gospel nonviolence as the center of our lives and our faith as Christians.

Last month, in a letter to Catholic News Service, Archbishop Joseph Takami of Nagasaki urged the people of the United States “to understand and practice the truth of peace that Christ teaches … the peace of Christ brought by his love [that is] stronger than death … We have to be convinced of the peace of Christ and continue our efforts to extend peace by working with people around the world to enable a world without nuclear weapons.”

Some years ago, my wife, our eight-year-old daughter and I visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the “epicenter of peace.” My wife Jean Stokan had been invited to represent Pax Christi USA at an Asian Conference for peace. We were hosted by Sister Filo Hirota, a member of the Japanese Catholic Council for Peace and Justice.

In the years since our visit, I have tried to write about that experience, but have been at a loss of words to describe the enormity of human suffering and evil represented by what happened there. The saving grace was to meet with survivors – the hibakusha – who were my daughter’s age when the bombs were dropped. That memory is seared forever in their hearts, and in their bodies and souls.

During our visit, Archbishop Takami of Nagasaki shared his own story with us. He was in his mother’s womb when the bomb dropped and identifies as a survivor “in utero.”

He took us to see the ruins of the cathedral, partially restored, and the names of 8,000 parishioners who died on that August 9, 1945 morning. He also showed us the burnt face of the wooden head of the grieving Virgin Mary, whose charred remains were buried in the rubble, discovered by a Japanese Trappist monk just days after the bombing and taken to his monastery before being returned to the cathedral decades later.

One of the places we visited with the archbishop was a shrine dedicated to Takashi Nagai, a medical doctor who survived the bombing of Nagasaki. He lived to care for the victims and returned to Ground Zero to build a hut where he lived with his two children and received people as he lay dying of cancer.

On Christmas Eve, 1945, just four months after the bombing, a “miracle” occurred. The bells from the cathedral of Nagasaki, which was destroyed in the bombing, rang! Parishioners who survived the bomb blast dug up the bells from beneath the atomic rubble and debris, hoisted them up and rang them, morning, noon, and night. Takashi Nagai wrote:

“Men and women of the world, never again plan war! With this atomic bomb, war can only mean suicide for the human race. From this atomic waste the people of Nagasaki confront the world and cry out: No more war! Let us follow the commandment of love and work together. The people of Nagasaki prostrate themselves before God and pray: Grant that Nagasaki may be the last atomic wilderness in the history of the world.”

As Christians, our reflection on the challenge of peace begins with our own encounter with the Crucified and Risen Christ. It is our encounter with the crucified Jesus – present in the crucified victims of war and violence – that helps shape our understanding of the urgency of peace and nonviolence. It is our experience of the risen Christ - in the survivors and witnesses who cry out for justice and for life – that gives expression to our deepest hopes for peace and reconciliation.

Our faith impels us to look at the world from the perspective of women and children, the poor and the refugees who are most often the victims of war, and to work with passion and urgency for an end to war and violence.

Violence in all its forms is sinful because it destroys human dignity and the common good. When violence becomes institutionalized – as poverty, war, racism or environmental destruction – it becomes a form of idolatry, denying the sovereignty of God over all of creation and the redeeming power of Jesus Christ’s love. Nothing short of the abolition of war and nuclear weapons from the earth must be our common goal. I find myself returning to the cries of the victims as they cry out, hoping that we never forget their impassioned pleas.

On the Feast of St. Francis, October 4, 1965, Pope Paul VI addressed the United Nations General Assembly and called for war to be abolished once and for all:

“If you want to be brothers [and sisters], let the weapons fall from your hands. You cannot love with weapons in your hands… It suffices to remember that the blood of millions of men and women, numberless and unheard of sufferings, useless slaughter and frightful ruin… unite you with an oath which must change the future history of the world: No more war, war never again! Peace, it is peace which must guide the destinies of peoples and of all humankind.”

Today, as we remember the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings, I remember a conversation I had with my father, a World War II Navy veteran whose aircraft carrier, the Bunker Hill, was hit May 11, 1945, off the coast of Okinawa. Two kamikaze planes struck the ship within 30 seconds and nearly sunk it. Four hundred men died in the attack, including the two kamikaze pilots.

While I was home, before visiting Japan, he told me a moving story. One of the men on his ship had recently died, and his grandchildren had discovered in his attic the personal belongings of the Japanese pilot who had crashed his plane into my father’s ship. There were some letters, some pictures, and the pilot’s watch. One of the grandchildren relocated to San Francisco, and there he contacted the Japanese Embassy to see if he could locate the family of the Japanese pilot so that they could meet in person. The day arrived, the two families met, and the personal belongings of the deceased pilot were returned to his family in a gesture of reconciliation.

I shared that story with our hosts in Japan. Nothing can undo the untold suffering that war brings on all sides, nor repair the destruction of precious human life caused by the atomic bombs dropped by the United States over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Only when we are joined in a common effort to abolish war and nuclear weapons might there be the real possibility of reconciliation and peace. But in that story, and that small gesture between those two families, formerly enemies, now reconciled – I find hope.

“No more war!” Takashi Nagai wrote from Ground Zero, before he died in 1951. For Christians, the victory over violence has already been won on the cross, but the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have paid a terrible cost, and the victims of all wars continue to be crucified.

Perhaps what is required of us today, to be faithful to the human family and to future generations, is to never again justify violence or be silent when nations go to war; we must actively and non-violently resist all war and preparations for war.

Then, perhaps, we might remember, every time we hear church bells ring, the bells of Nagasaki, and imagine the faithful survivors gathered around the ruins of the Nagasaki cathedral that Christmas Eve, 1945, as they invite us once again to make our own this ancient dream of peace: “They shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not life up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore” (Is 2:4).

Scott Wright is director of the Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach in Washington D.C.

Copyright © 2025 Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach, Washington, D.C.